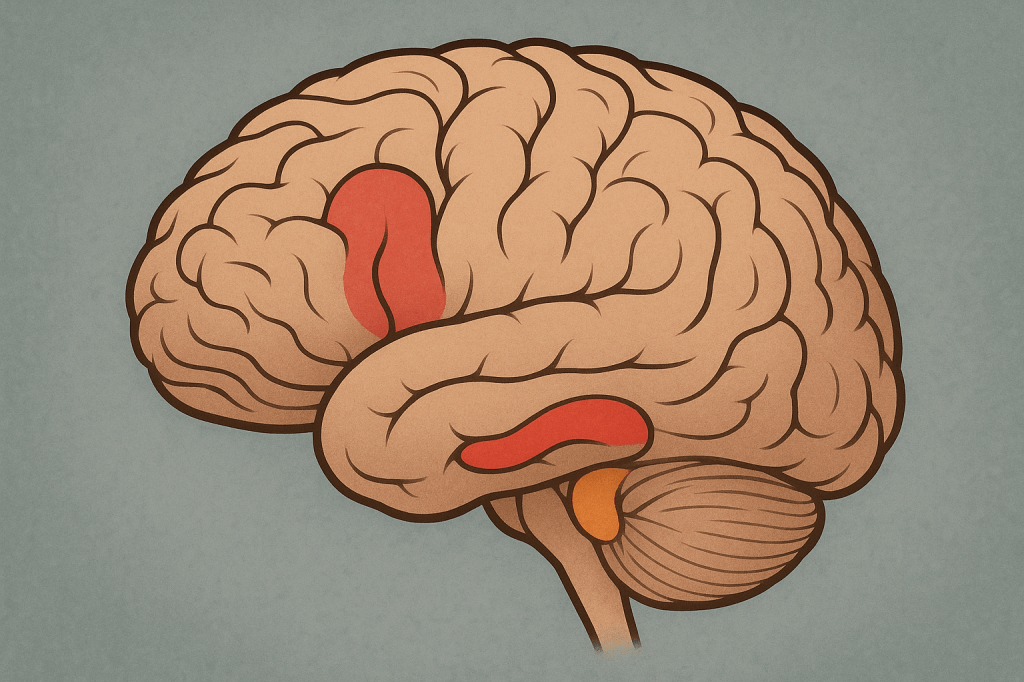

Brain scans show hippocampus and amygdala most affected

—When bipolar disorder strikes children for the first time as mania, it can leave a mark deep inside the brain. New research from Zhejiang University shows key emotion and memory centers are smaller in these young patients than in those whose illness begins with depression or in healthy kids.

The study, published Nov. 1, 2024, in BMC Psychiatry, examined 59 children and adolescents using high-resolution MRI. Thirteen had experienced a first manic episode, 28 a first depressive episode, and 18 were healthy controls.

All underwent brain scans at three collaborating hospitals. Using advanced imaging software called FreeSurfer, researchers measured the volume of subcortical structures — regions below the brain’s outer layer that handle memory, motivation and emotional control.

Across the board, patients with bipolar disorder had larger fluid-filled spaces known as the third and fourth ventricles compared with healthy children. But the clearest differences appeared in the mania-onset group.

These patients had smaller volumes in the left thalamus, both sides of the hippocampus, and the right amygdala.

The hippocampus, an essential part of the limbic system, plays a key role in regulating affective states, complex cognitive processes, and stress response. The amygdala’s main function is vigilance and emotional regulation — areas critical for processing feelings, forming memories, and routing sensory information.

When scientists zoomed in on subregions, the picture sharpened further. The hippocampus head and tail were reduced in size, along with parts of the amygdala known as the accessory-basal and cortico-amygdaloid nuclei.

These alterations might present a trait feature of mania-onset pediatric bipolar disorder, the authors wrote, suggesting such changes may be stable characteristics rather than temporary effects.

No similar shrinkage appeared in the depression-onset group, pointing to possible biological differences between the two forms of early bipolar disorder. That distinction could help doctors tailor treatment sooner and monitor the most vulnerable brain regions over time.

Bipolar disorder, marked by swings between extreme highs and lows, can be especially disruptive when it starts in childhood.

Mania in young people often brings rapid speech, bursts of energy, and risky behavior, while depression can cause withdrawal, fatigue, and hopelessness.

By linking these behaviors to measurable brain differences, the research adds another piece to the puzzle. The team hopes future studies will follow patients over years to see whether targeted therapy, medication, or lifestyle changes can slow or prevent further brain changes.

Comment from a reader suffering from bipolar disorder: Well, I don’t think I had a manic episode until much later in life, but I am experiencing, brain fog, lack of focus, and short-term memory loss. It’s very hard to deal with.

Leave a comment