A comedian who quit—and started seeing in color

Sydney-based stand-up Sam Kissajukian walked away from comedy in 2021, rented an abandoned cake factory, and began to paint. Over the next six months, he produced more than 300 large-scale works—an explosion of color, gesture, and pattern that doctors later described to him as a sustained manic episode. That improbable creative detour became the seed of 300 Paintings, a hybrid solo show and gallery experience now touring major U.S. theaters.

Kissajukian describes himself as a comedian and visual artist who has toured widely across Australia, the U.S., the U.K., and Europe—framing the art practice as an extension rather than a departure: Making contemporary art is funnier than being a comedian.

The origin story: six months, 300 canvases

Accounts across the press align on the core timeline: after leaving stand-up, Kissajukian painted relentlessly for half a year, amassing 300+ works while unknowingly documenting his mental state in real time. The show reconstructs that period with projected images of the paintings, storytelling, and a candid debrief about bipolar disorder, treatment, and recovery.

The work resists both romanticizing mania and reducing it to pathology. Reviews from theater critics converge on a portrait of artistic urgency threaded with risk: a wildly creative yet dangerous phase that led to diagnosis, therapy, and medication—and, eventually, a show that makes sense of it all.

What the paintings reveal about mania

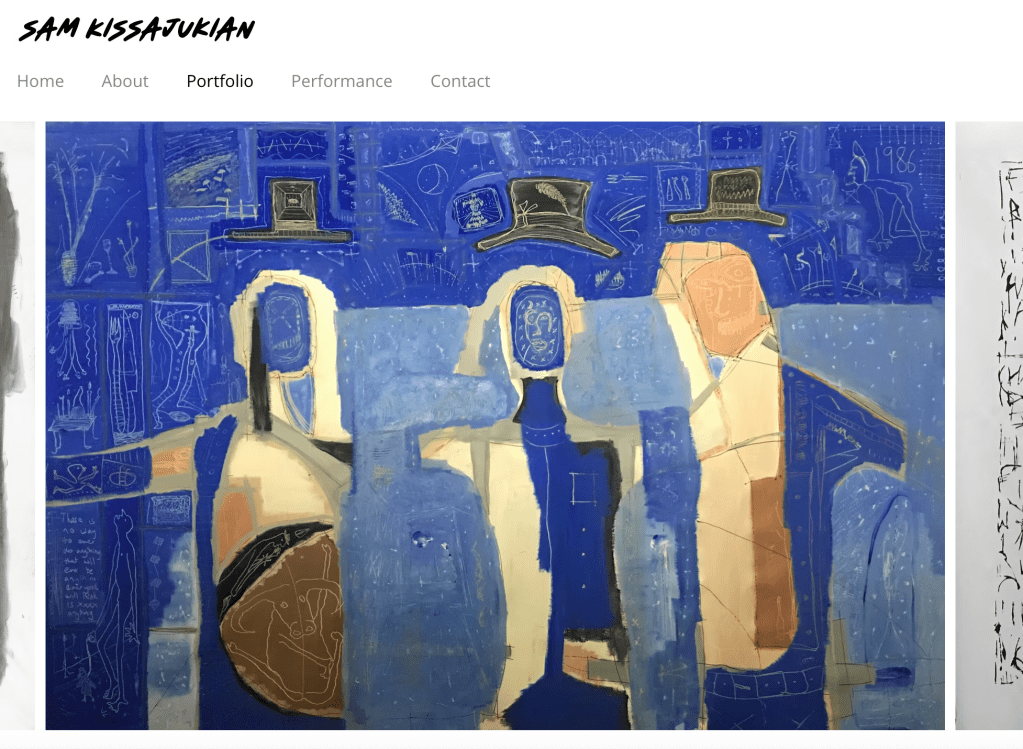

Visually, the canvases—shown in slides during the performance—chart intensity, speed, and shifting motif sets. Viewers see serial patterns, thick impasto, and layered mark-making accelerate and fracture. In multiple write-ups, critics describe the art as a kind of EEG in pigment: the brushwork’s tempo and repetition become data about a mind in flight. Kissajukian leans into that reading onstage, treating the question Is this masterpiece or manic episode? as the point—then unpacking how both can be true.

He also pushes back on pity, according to one review: Don’t feel sorry for me; I’m here, aren’t I? That attitude shapes the show’s tone—curious, disarming, and often very funny—while keeping the conversation grounded in agency and long-term management rather than spectacle.

The show: stand-up timing meets gallery talk

300 Paintings plays like a cross between a comedy special, an artist’s talk, and a mental-health seminar. The Vineyard Theatre in New York mounted the piece in late 2024; American Repertory Theater in Cambridge and McCarter Theatre Center in Princeton welcomed it in fall 2025 as part of a U.S. tour. The evening runs around 80 minutes and integrates a slideshow of the work, personal narrative, and Q&A-style accessibility—Kissajukian invites audiences to connect after the show.

Radio and press coverage emphasize how the format de-mystifies bipolar disorder. One public radio segment framed it as an attempt to understand the connections between art and mental health, while other outlets highlighted its mix of humor and frank disclosure about diagnosis, therapy, and medication.

Beyond the trope of the ‘mad artist’

Kissajukian’s story risks slotting into the oldest cliché in art history. He addresses that head-on. Interviews show him insisting on management strategies, not myth: identifying his mood “rules,” recognizing cognitive speed and risk behaviors, and crediting psychiatric care with transforming aftermath into insight. The paintings’ existence isn’t proof that mania is desirable; the show’s existence is proof that reflection is possible.

This distinction matters. Mania can feel superhuman—fewer inhibitions, surges of novelty, a flood of ideas—and yet it is also corrosive, dangerous, and unsustainable. 300 Paintings holds both truths at once, neither glamorizing nor scolding. For audiences with lived experience, that balance reads as respect. For those without, it’s a primer in nuance.

Kissajukian’s project lands squarely at the intersection of neuroscience, psychology, and culture. It offers a real-world case study of mood-state phenomenology rendered in paint and performance. For clinicians, it’s an accessible narrative patients can engage with. For artists, it’s a mirror with circuit breakers built in. For everyone, it’s proof that post-episode meaning-making is itself a creative act.

Sources

- Sam Kissajukian official site — https://samkissajukian.com

- Vineyard Theatre — https://vineyardtheatre.org

- American Repertory Theater — https://americanrepertorytheater.org

- McCarter Theatre Center — https://www.mccarter.org

- Cambridge Day review — https://www.cambridgeday.com

- TheaterMania — https://www.theatermania.com

- DC Theater Arts — https://dctheaterarts.org

- WNYC Radio — https://www.wnyc.org

- Boston Globe Arts — https://www.bostonglobe.com

Recent articles

- From Stranger Things to Real-Life Resilience: He confronts Bipolar Challenges

- Mental Health Experts Raise Alarms About AI Chatbots Fueling Psychosis

- AI Listens For Mood Swings In The Voices Of Those With Bipolar Disorder

- Hospital Visits For Hallucinogens Linked to Sharp Rise in Mania

- Jason Silva Says Hypomania is A Driver of Creativity

Comment from a reader: Wow, Sam did some amazing artwork here. He is lucky to have used his creativity during his manic episode to create artwork that tells a story.

Leave a comment